No, this is not all about Toulouse, but it could be! He’s such a good little furry guy!

In case you are interested, I’m summarizing how a PET scan can help us monitor metastatic breast cancer. If you are not in a science-y mood, you might want to pass on this post.

A PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan is often used to detect cancer. It is also commonly used to diagnose heart disease and brain conditions. With cancer it is used to determine if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (metastasized). [Tomography = a technique for displaying a representation of a cross section through a human body or other solid object.]

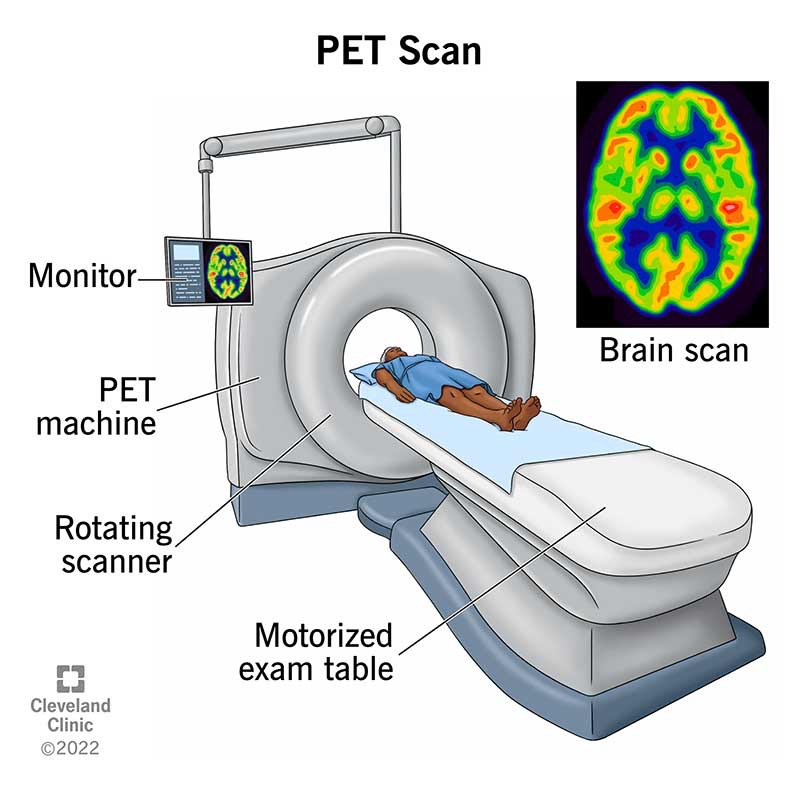

A PET scan detects cellular changes in organs and tissues earlier than CT and MRI scans. The scan is painless, although sometimes people can feel claustrophobic as their head moves through the large tube. The machine used to do the scan is shown in this diagram from the Cleveland Clinic.

Prior to the scan, an injection of a glucose-based radiotracer is given. A person has to wait about 45 minutes after the injection before the scan is started. This gives the radiotracer time to circulate through the blood stream and body.

A PET scan can take 30 minutes to 2 hours depending on what exactly is being examined. The radioactive tracer allows the machine to detect diseased cells. Diseased cells will uptake (or collect) more of the glucose radioactive tracer because they are more metabolically active than healthy cells. This increased uptake is visualized as brighter spots on the imaging.

The most common radiotracer used in PET scans is fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Once it’s inside the cell, it’s trapped. The PET scan machine can quantify the amount of tracer uptake using SUV. SUV (Standard Uptake Value) is a quantitative measure used to assess the concentration of the tracer.

SUV represents the ratio of the amount of radioactive tracer in a specific region of interest (like a tumor) to the amount of tracer that would be expected in a similar volume of normal tissue, taking into account the injected dose and patient’s weight.

Changes in the SUV number over time can help determine how well a patient is responding to cancer treatment.

In an imaging report, SUV numbers are reported. The radiologist or oncologist can then compare the SUV numbers to previous PET scans to determine if the cancer is more active (higher SUV number) or less active or inactive (lower SUV number).

While all of this sounds very concrete and specific, it’s still just an approximation of what is happening in the body. Results from a PET scan are used along with other factors such as how an individual is feeling, whether or not there is pain present, and blood work results.

PET-CT

Sometimes a PET scan is done in conjunction with a CT scan. The same machine does both of them and a patient would have both done during the single scanning session. The combination of both a PET and CT scan produces a three-dimensional image that allows for a more accurate diagnosis.

A CT scan is Computed Tomography and uses x-rays to get a detailed view inside the body. It produces still images of organs and body structures (such as bones). Sometimes it’s referred to as a CAT scan – it’s the same thing. CAT = Computed Axial Tomography.

Instead of creating a flat, 2D image, a CT scan takes dozens to hundreds of images of your body. To get these images, a CT machine takes X-ray pictures as it revolves around you.

After a scan is completed, the technician makes sure the images look ok and then it is sent to a radiologist to interpret and read. The radiologist writes a report of what they see, ideally comparing it to previous PET or PET-CT scans. That report is then forwarded to the oncologist and the patient. The oncologist and patient, together, determine what changes to make to treatment (or not) based on the scan results as well as other factors such as how the patient is feeling and blood work.